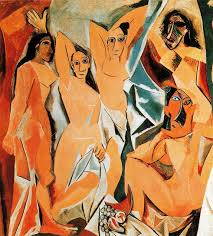

Imagine walking into a Paris studio in 1907. On the wall is a massive canvas titled Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon). At first glance, you might expect a graceful scene of elegance. Instead, five women confront you with fractured bodies, jagged edges, and faces like masks. Some critics called it ugly. Others thought it was madness. But there was meaning behind the name.

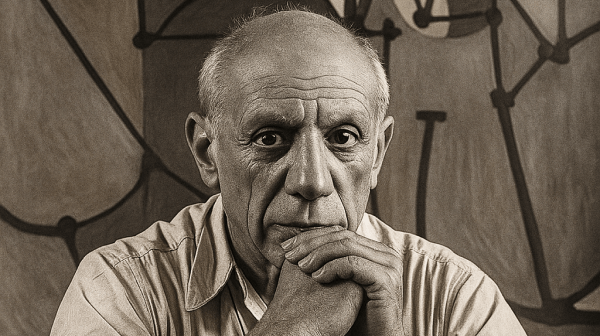

When we think of art that changed the world, Pablo Picasso almost always comes to mind. He wasn’t just a painter; he was a restless creator, a rule-breaker, and at times, even a troublemaker in the eyes of tradition. Through Cubism, he didn’t simply start a new art style; he gave humanity a new way to see.

Who was Picasso?

Pablo RuizPicasso was born in 1818 in Málaga, Spain, to José Ruiz Blasco, a painter and art teacher, and María Picasso y López, a dedicated homemaker. Art surrounded him from the very beginning—his father not only taught drawing at the local School of Fine Arts but also painted birds, especially pigeons. It’s said that Pablo’s first word was “piz” (short for lápiz, the Spanish word for pencil), as if destiny itself pointed him toward a life in Art.

Although his father’s surname was Ruiz, Pablo chose to sign his works with his mother’s name, Picasso. It was shorter, more distinctive, and carried a rhythm that stood out in the art world. “Ruiz” was a common Spanish surname, but “Picasso” had character—it was unforgettable. This decision was one of the first ways young Pablo began shaping not just his art, but his identity.

By the age of nine, Picasso had completed his first painting, and at 13, he was already admitted into prestigious art schools in Barcelona and Madrid. His talent was undeniable, but Picasso was not interested in staying inside the neat boundaries of academic training. He was ambitious, curious, and always hungry for more. By his early twenties, he had lived through phases that reflected not just his technique but also his emotions: the Blue Period, with its melancholic tones inspired by loss and hardship, and the Rose Period, warmer and more tender, filled with circus performers and dreamers. Each phase was like a diary written in paint. Yet Picasso was still searching for something bigger, something the world had never seen.

Breaking Away from Tradition

At the start of the 20th century, much of Western art was still tied to realism: perspective, proportion, and the illusion of depth. Artists were judged by how closely their paintings mirrored life. But for Picasso, the canvas wasn’t meant to copy reality; it was meant to question it.

He had been influenced by African and Iberian sculpture, which opened his eyes to bold shapes and symbolic forms. He started to wonder: What if a painting could show us more than one perspective at the same time? What if we broke down the world into pieces and put it back together differently?

The Earthquake: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

In 1907, Picasso shocked even his closest artist friends with a painting that looked like nothing they had ever seen: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon). Gone were the soft curves and naturalistic faces. Instead, jagged lines, fractured bodies, and mask-like faces stared back at the viewer.

The word “Avignon” pointed not to the French city, but to Carrer d’Avinyó, a street in Barcelona infamous for its brothels. Picasso drew on memories of the women he had seen there in his youth—women whose presence carried both allure and unease. In the painting, their stares are not seductive but confrontational, almost defiant.

That tension was deeply personal. Picasso lived in an era when syphilis was rampant across Europe, and he consistently carried anxiety about the disease. To many art historians, the distorted, mask-like faces of the women reflect that inner conflict: sexuality as both desire and danger.

At the same time, Picasso was absorbing new cultural influences. African masks and Iberian sculptures, which he studied in Paris museums, struck him with their raw power and abstraction. He wove their forms into his Demoiselles (young ladies), reshaping the women into fractured, almost totemic figures that felt both human and otherworldly.

The result was not just another canvas, but a rebellion. Picasso wasn’t painting beauty as tradition demanded—he was dismantling it, reimagining it, and daring the world to see differently. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was the earthquake that cracked open the door to Cubism.

The painting was confrontational, unsettling—even ugly to some. But it was also revolutionary. For the first time, Picasso had dismantled traditional perspective and created something radically new. This work was the spark that lit the fire of Cubism.

Cubism: A New Way of Seeing

Together with fellow painter Georges Braque, Picasso began to reimagine the world through fragments. Instead of showing a guitar, a bottle, or a human face from just one angle, they painted them as if you could see all sides at once.

Cubism developed in two phases:

- Analytical Cubism (1908–1912): muted colors, broken forms, and layers upon layers of perspective. Imagine peeling back the world and showing its hidden sides.

- Synthetic Cubism (1912 onwards): bolder, brighter, and playful—this phase introduced collage and brought everyday materials into fine art.

What they created was not just a style, but a philosophy. Cubism told us: reality is never just one angle, one truth, or one viewpoint.

Why It Still Matters

Cubism was the seed from which modern art grew. It opened the doors for movements like Futurism, Abstract Expressionism, and even the digital abstractions we see today. Picasso didn’t just paint shapes—he painted possibilities.

Picasso’s Legacy

By daring to break tradition, Picasso gave artists and the world permission to see differently. His work remains a reminder that sometimes the boldest act of creativity is to take what exists, pull it apart, and rebuild it in your own way.

Final Thoughts

Picasso’s journey teaches us something deeply human: reinvention is possible at every stage. From his childhood genius to his radical experiments, he showed us that art (and life) is not about repeating what already exists, but about daring to imagine what could be.

If Picasso were alive today, how do you think he’d use technology—AI, digital art, or VR to revolutionize creativity all over again? Share your thoughts in the comments after reading the full story.