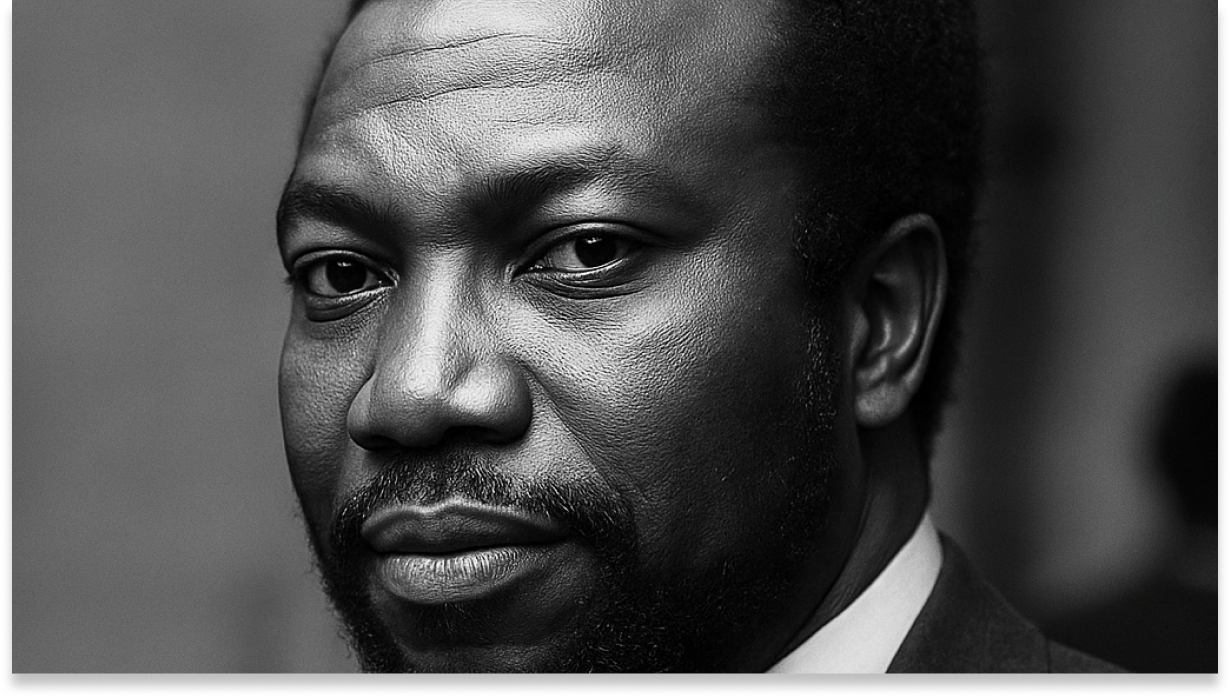

In the story of modern African art, Ben Enwonwu stands as a towering figure—a man who carried the weight of tradition in one hand and the possibilities of modernity in the other. Celebrated as “Africa’s Picasso” but known authentically as a pioneer in his own right, Enwonwu reshaped how the world viewed African creativity. His career was not simply about making art; it was about giving Africa a voice on the global stage, a voice that drew from the depth of his roots in Onitsha and echoed far beyond Nigeria’s borders.

Background and Early Life

Odinigwe Benedict Chukwukadibia Enwonwu MBE, better known as Ben Enwonwu, was born on July 14, 1917, in Onitsha, a vibrant riverside town in southeastern Nigeria popularly known for its cultural traditions and artistry. He came into the world as a twin in a noble Igbo family.

His father, Omenka Odigwe Emeka Enwonwu, was a master sculptor whose works—ancestral figures, ritual masks, ceremonial staffs—were integral to Igbo religious and civic life. Watching his father carve, young Ben absorbed the rhythm, patience, and spiritual significance of art. He learned that every line, every curve, carried meaning beyond mere appearance.

His mother, Chinyelugo Iyom Nweze, was a respected cloth merchant. Through her, Ben developed an eye for patterns, color harmonies, and the aesthetic pulse of everyday life. Her marketplace was a living canvas of textures and movement, teaching him the subtle ways art could reflect culture, commerce, and identity. Together, his parents provided the dual foundation that would now define his artistic vision: his father imparted tradition and spirituality; his mother instilled vibrancy, rhythm, and a connection to lived experience.

Tragedy struck early: his father died in 1921, when Ben was only four. Yet the tools, lessons, and legacy of his father became guiding lights in his life, a bridge from heritage to innovation.

Education and Formation

Enwonwu’s natural talent drew attention in school, particularly under the mentorship of Kenneth C. Murray, a British art educator who championed African craft and tradition. Murray encouraged Enwonwu to see the richness of his heritage as a foundation for modern creativity.

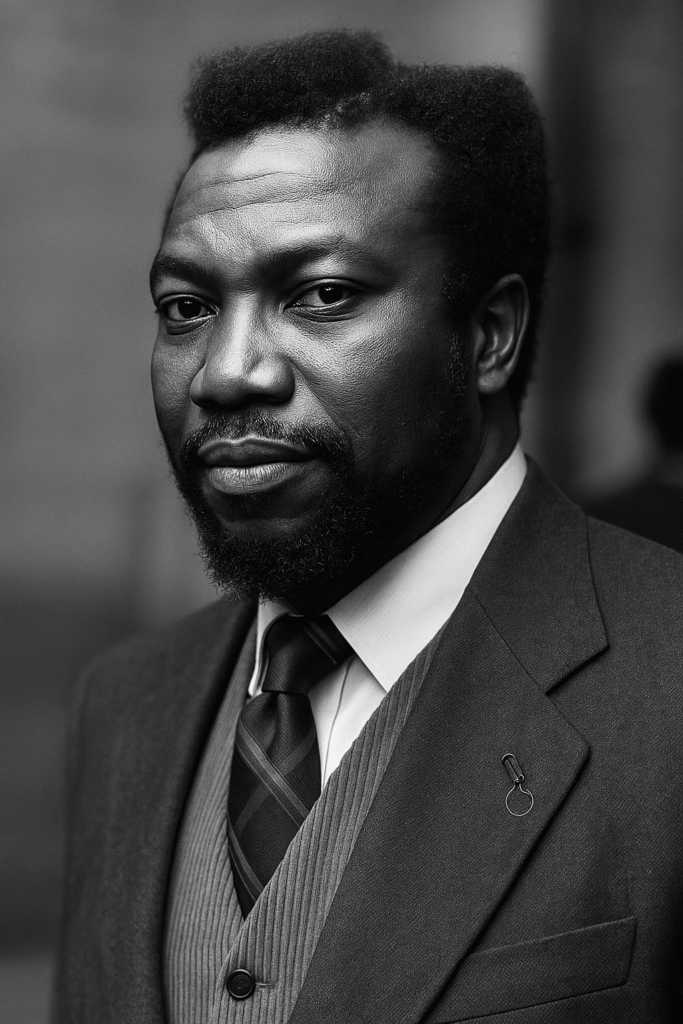

In 1944, Enwonwu won a Shell/British Council scholarship to study in London, attending Goldsmiths College and the Slade School of Fine Art. There, he encountered European modernism, mastering abstraction, proportion, and the technical rigor of Western painting and sculpture. Yet, even as he absorbed these lessons, he remained rooted in his parents’ legacy. Modernism, to him, was not imitation—it was transformation: a tool to elevate African tradition into global dialogue.

Art Style and Inspirations

Ben Enwonwu’s artistic style was a harmonious fusion of African heritage and Western modernism. From his father, he inherited sculptural elongation, symbolic abstraction, and the understanding that art could be spiritual and communal. From his mother, he drew inspiration for color, texture, and dynamic pattern, learning to see movement in fabrics, markets, and daily life. European modernism offered him scale, abstraction, and formal experimentation.

His subjects were equally diverse yet unified in purpose: dancers, masquerades, market women, deities, and national figures. Every piece aimed to capture not just form, but spirit, rhythm, and cultural identity. Enwonwu himself said that art must “speak for the spirit of Africa,” a conviction rooted in the dual legacy of his parents and his early life in southeastern Nigeria.

Pivoting African Art

Operating in the mid-20th century, a period of colonial rule, nationalist movements, and the early stirrings of independence, Enwonwu realized that African art had to do more than preserve tradition—it had to claim relevance in a global context. Walking through his studio in Lagos, visitors saw the almost theatrical energy of his work: wooden carvings lined the walls, unfinished canvases leaned against the floor, and the smell of oil paint and wood shavings filled the air. He moved between sculptures and paintings, chiseling a figure, then stepping back to paint a market woman, speaking to apprentices as he worked. “Observe the soul,” he would tell them. “The body is nothing without it.”

Several pivotal experiences fueled this mission. Studying in London exposed him to European modernism, where he realized that African aesthetics could engage with global artistic movements without sacrificing authenticity. At the same time, the growing Nigerian independence movement gave his work political and cultural urgency. Art could now assert African dignity and intellectual capacity to a world that still dismissed it.

Perhaps the most symbolic pivot occurred in 1957, when Enwonwu was commissioned to paint Queen Elizabeth II during her visit to Nigeria. Standing before the British monarch, he subtly infused African sensibilities into the portrait, asserting that African creativity was capable of sophistication, nuance, and global relevance. From that moment on, Enwonwu’s work became a bridge between past and present, tradition and modernity, Africa and the world.

Through exhibitions across Europe, America, and Africa, and through mentoring younger Nigerian artists, Enwonwu repositioned African art as respected, contemporary, and globally significant. His mission was clear: African art was no longer an artifact; it was alive, evolving, and indispensable.

Major Works

- Anyanwu (1954) – Bronze sculpture at the Nigerian National Museum, embodying rebirth and resilience.

- Portrait of Queen Elizabeth II (1957) – A groundbreaking work blending African and European aesthetics.

- Tutu (1973) – Portraits of Princess Adetutu Ademiluyi, exuding grace, power, and post-war reconciliation.

- Sango (1964) – Interpretation of the Yoruba god of thunder, merging myth and modern form.

Awards and Recognition

Enwonwu’s brilliance was acknowledged both nationally and internationally:

- MBE (Member of the British Empire), 1958

- Nigerian National Order of Merit, 1980

- Various honors from Senegal and academic fellowships in Nigeria and abroad.

These awards reflected not just his technical skill but his role as a cultural ambassador, reshaping the world’s perception of African creativity.

Later Years and Death

Even after a cancer diagnosis in the 1980s slowed his sculpting, Enwonwu continued painting and mentoring. In his final Lagos studio, he would greet students warmly, guiding their hands over clay and canvas, reminding them that every mark carried responsibility and meaning. On 5 February 1994, he passed away in Ikoyi at age 76. The chisels of his father, once inherited, had become a global voice through Ben’s art.

Legacy

Ben Enwonwu’s story is one of vision, courage, and bridging worlds. From his father’s sacred carvings to his mother’s vibrant fabrics, from the markets of Onitsha to London galleries, he transformed African art in the 20th century. His works continue to inspire new generations of artists, proving that African art is not only a heritage to be preserved but a living, evolving force.

Central to his enduring influence is the Ben Enwonwu Foundation (BEF), established in 2003 under the stewardship of his son, Oliver Enwonwu. The foundation works to preserve and promote his life and work, support emerging African artists, facilitate art research, and provide mentorship programs, internships, and exhibitions. Initiatives like the “Point of View” series foster dialogue on contemporary art while bridging African and global creative communities. Through the foundation, Enwonwu’s mission lives on, ensuring that his vision continues to inspire, educate, and empower.

He remains a trailblazer, visionary, and master of African modernism, reminding the world that true art is a dialogue between past, present, and future.